I wrote this piece for Tahrir Squared before today’s court verdict to suspend Egypt’s upcoming parliamentary election, still I think it is relevant and I hope it provides the leaders of opposition parties in Egypt with some food for thought. Let me know what do you think; I welcome your feedbacks and comments.

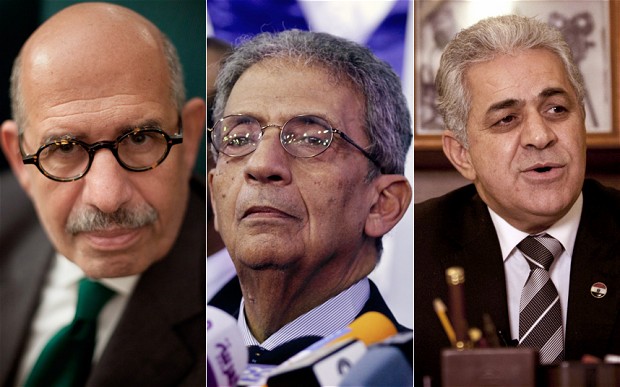

(Photo: AP)

“Juvenile,” “self-defeating,” “myopic,” “not smart” — since Egypt’s main opposition coalition, the National Salvation Front (NSF), has announced that they will boycott the next parliamentary elections, a sustained, ferocious barrage of criticism has been unleashed against them. The Egyptian opposition is not currently at an enviable place: youth activists are frustrated, pundits are critical, Islamists are piling accusations, and the U.S. leaders are not impressed, not to mention the valid fear of breaking ranks from one or two of the partners within the coalition umbrella.

There are good reasons to criticize the Egyptian opposition; their performance since the fall of Mubarak’s regime has been shambolic, to say the least, for many reasons: the lack of clear strategy, being led by the protest movement, and the inability to provide the Egyptian public with a viable alternative to the Islamist project. There are also legitimate questions about the validity of a boycott as an effective tool for political gain; the experience of boycotting in Latin America for example, could be used to highlight the risks of boycotts. Even the Egyptian experience over the last two years demonstrates how a campaign of active boycotting may not be successful or even popular among the public.

However, it might be more beneficial to look at the issue from a different perspective and discuss what the opposition would gain from participating in the upcoming parliamentary elections. This might help settle the question of whether a boycott should occur, while avoiding the pitfalls of faulty parallels.

There are three possible outcomes for the NSF if they decide to run in the elections:

A bad loss: This would be the case if the NSF fails to match the previous results of the 2011 election, when the parties within the NSF gained about 25% of the seats. This is a very plausible outcome, despite recent hopeful speculations of better results:

- Although there is a growing resentment against the Brotherhood among the public, there is not enough evidence that this resentment will be channeled towards more votes to the NSF. The opposition, with its current fragile structure and internal divisions, stands a greater chance to perform badly in the next election, as many of its supporters are not impressed with its current performance. Additionally, to many, the NSF remains either an unknown entity or an unpopular one: according to a recent new poll by the independent Egyptian polling group Baseera, some 35% of Egyptians have never heard of the NSF, and among those who had, only 35% said they supported the opposition group. This dissatisfaction may be compounded if the NSF revokes its boycott without gaining any compromises from President Morsi on their already-stated demands.

- Some may argue that the division among the Islamists and the recent fall out between the Salafi Nour party and the Muslim Brotherhood could benefit the NSF. This is unlikely for two reasons. On one hand, the presence of liberal opponents fighting for seats in the parliament would encourage the Islamists to rise above their differences, and unite against the liberals in every contested seat. On the other hand, the core supporters of the Islamists may prefer to shop around between the Muslim Brotherhood and the various Salafi parties; abandoning the Islamic project and voting for a non-Islamist party is highly unlikely.

- Undecided voters are another factor; there are many speculations about how this significant section of the Egyptian public will vote. Some may swing to the right and vote for any of the Salafi parties, which is a very viable scenario in rural areas where disenchantment with the government is high; others, may decide to stay at home and not vote at all. There are no reasons to believe that the turnout in the next parliamentary elections would be better than that of the constitutional referendum (32%). Bearing in mind the wave of civil disobedience, particularly in the Canal region, a de-facto boycott with less than 25% participation is a valid possibility. Can one imagine an election campaign in Port Said or Mansoura? It is difficult to entertain such an eventuality.

A loss but with consolidated gains: Can the NSF match their 2011 performance or even do better? The notion that the opposition may make significant gains in the elections is highly unlikely to become a reality if the Brotherhood refuses to compromise and insists on rejecting the main demands previously put forward by the opposition’s representatives. Therefore, it is very important that the NSF secures some pre-election gains to boost its popularity among the public.

Even if the public rallies behind the opposition and they manage to gain a decent number of seats, how would this benefit the opposition? Will being in parliament be better than their current political existence, restricted to TV studios and press conferences? Again, this is doubtful. Surely, the bickering would move from the TV studios to the parliament but the outcome would remain unchanged. Any perceived liberal clause in any proposed law will be contested, and vetoed by the Brotherhood and the Salafists. It is hard to conceive that the opposition would stay united after the election, playing a successful role in dividing the Brotherhood and the Salafis under the Parliament’s dome, when they have clearly failed to do so outside of the parliament.

An election victory: The NSF scoring an election victory is highly unlikely. A united NSF that manages to gear enough support to beat all Islamist parties and win the majority of seats in the parliament (even with a narrow margin) would be an improbable outcome. It is also doubtful that a victory by the NSF would save the country or end the turmoil for many reasons, including:

- The first outcome of any opposition victory is its formal disintegration, and endless bickering among its parties about what to do next. There is no common vision between the leftist, liberal, and ex-regime (Felool) parts of the NSF, other than their vehemently anti-Muslim Brotherhood stance.

- An opposition-dominant parliament would still have the Presidency to deal with, and would also have to deal with the Islamists parties that will almost certainly dispute the results, blame it on the current wave of violence, and engage in a ferocious fight to regain power.

- On the other hand, the most important challenge for a victorious opposition would be inheriting the current government’s mess, with the ticking bomb of the collapsing economy and the disintegrated law and order. It is almost impossible that the drained opposition after a fiercely contested election would have the time to provide a clear alternative plan to deal with both eminent challenges without turning the public against it.

Egypt is living proof that one cannot manufacture an ideal government or an ideal opposition; rather, one must deal with what one has at the moment and make decisions that could be painful and even risky. Judging by Egypt’s haphazard politics, the NSF’s fragile unity, and without serious compromises from the Brotherhood’s leadership that can diffuse the current inflammatory dynamics, a tactical boycott of the upcoming parliamentary elections by the NSF appears to be a wise option.

Nonetheless, it is crucial to understand that a boycott will not stand any chance of success unless all opposition parties are united in adopting it. Any last-minute break of the ranks, with one or more parties deciding to run in the election, would be suicidal with irreparable, long-lasting damage.

In this scenario, a boycott can be viewed as a form of sabbatical leave to break up with the politics of bickering and violence, and to allow the opposition to reset their own playbook away from the current majoritarian game of the Brotherhood. The opposition must dissociate itself from the growing wave of violence in Egypt, and initiate a different, well-orchestrated, “peaceful,” civil disobedience campaign, including an economic boycott of products, and businesses of the Islamist elite and their interests around the country. Such a campaign would help each sub–group within the opposition umbrella to boost its popularity base. It would also convince the public that the NSF is not just after any victory, but after effective, cleaner politics away from the Islamists’ opportunism and monopolistic approach. Such a boycott campaign is not without its risks, but the same can be said for participation in a dodgy, violent election process. Islamists have sucked the oxygen out of Egypt’s political scene; it is about time for the opposition to reorganize and come back with some fresh air.

Reblogged this on Ned Hamson Second Line View of the News.

LikeLike