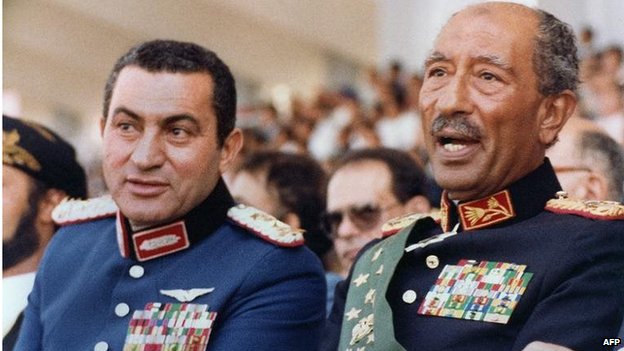

( Photo via BBC)

Initially published in NOW.

29 November, an Egyptian court dismissed murder charges against Egypt’s former president, Hosni Mubarak, in connection with the killing of protesters in the 2011 uprising that ended his nearly three-decade reign.

The verdict was a testimony of what is wrong with the entire country, its leadership, the judicial system, both Islamist and non-Islamist politicians, and, more importantly, its youth. As a child, I viewed Mubarak as the man who had ruined my Cairo neighborhood of Heliopolis. As I grew up, I started to understand that his tenure in power had far-reaching consequences. Mubarak’s rule didn’t just ruin Egypt; he rendered the country incapable of recovering or moving away from his legacy.

The 1981 anniversary of the October 6 War in 1973 was supposed to be the usual annual celebration, but destiny had a different script. President Sadat was assassinated, and with his death the residents of Heliopolis woke to a new reality—their neighbor, Mubarak, was now the new president of Egypt, and his new promotion brought new security measures to the whole area. The Metro line that used to pass near his house had to be redirected. The area became inundated with plainclothes security personnel, an event that changed the lives of Mubarak’s next-door neighbors beyond recognition; even getting in and out of the house became tricky, to say nothing of socializing. Every part of Heliopolis was geared for one task — serving Mubarak. Gradually, and throughout his 30 years of rule, everything else in Egypt was exclusively geared for one task — serving Mubarak.

Arguably, Mubarak was not Egypt’s worst dictator. His style was mellower than Nasser’s and less theatrical than Sadat’s. Nonetheless, his toxic impact stemmed from his determination to spread his own uninspiring character to the country as a whole. As an anti-intellectual, Mubarak focused his efforts on turning Egypt into a shallow, weak, and uninspiring state incapable of producing a competitor that might challenge his authority. He ruled with a distinctive shabbiness that made every aspect of the nation, from politics and education to spirituality and art, tired and uninspired.

During Mubarak’s rule, Islamists focused on the survival of their ideology rather than transforming it into a viable political alternative capable of successful governance. Non–Islamists focused on the survival of their lifestyle amid the rise of Islamism, and couldn’t have cared less about the core principals of classic liberalism they pretended their basic beliefs were. Furthermore, the climate of materialism and corruption Mubarak encouraged reduced art and culture to a mere tool for entertainment, not intellectual depth.

The reaction to Mubarak’s acquittal highlights the impact his toxic legacy has had on post-Mubarak Egypt. A day before the court verdict, some Islamist groups staged an Islamic identity protest, which was supported by the Muslim Brotherhood. Islamists fully understand that playing the identity card at such crucial moments is a divisive move that will alienate many Egyptians. Their goal, however, is not unity, but to enforce the perception of the power of their groups.

Their reaction after the verdict was no more than an angry rant at their non-Islamist nemeses, whom they blame for the acquittal verdict. The non-Islamist response, articulated with shock and anger, has nevertheless been ineffectual. Their knee-jerk reactions have yielded nothing more than a few angry protests following the verdict and a call for separate demonstrations later. Resorting to the well-worn tool of protest signals an inability to create cohesive answers to Egypt’s stagnant politics, or to force the current leadership under President Sisi to embrace serious democratic reforms.

The failure of Egypt to move away from the past and create a better future is testimony of the depth of the cancer Mubarak inflicted on Egypt and the resilient destructiveness of his three decades in power. Both Morsi and Sisi are products of Mubarak’s tenure. Morsi was the Islamist version: weak and lacking charisma, like Mubarak he focused solely on the survival and dominance of his group, instead of guarding the vulnerable transition toward genuine, inclusive democracy.

Sisi’s rise also stems from Mubarak’s legacy. Thirty years of uncharismatic rule has made the smallest hint of charisma very appealing to ordinary Egyptians, even if it is underpinned by sheer ruthlessness.

Mubarak’s verdict in itself is meaningless. Egyptians already issued their verdict in January 2011 when they poured spontaneously into Tahrir Square demanding Mubarak’s departure. Their chanting of “irhal,” or “leave,” was more powerful than any court verdict. Mubarak will forever remain guilty even if all the courts on Earth acquit him. Last week’s court ruling, in reality, was a verdict against Egypt. It simply shows how crippled and confused Egypt still is.

Sisi the strong man has inherited some of Mubarak’s greyish traits. He won’t pursue action against Mubarak, but plans instead to issue a decree that bans “insulting” the 25 January 25. His conflicting messages will be resented by those both anti and pro-Mubarak. Surely the president of Egypt understands that Mubarak’s supporters insult the 25 January revolution on a daily basis. The way in which Sisi intends to handle Mubarak’s supporters is a tough challenge that may shape his tenure in power.

Egypt does not need judicial and security reforms alone: Egypt’s mindset and way of thinking needs a complete de-Mubarakization. Both Islamists and non-Islamists alike should stop pointing fingers and making cross-accusations. Both should steer clear of opportunism and divisive politics.

The battle to salvage Egypt may take generations. We have to start from scratch by teaching our youth basic political values such as strategies for inclusiveness and leadership skills. The next parliamentary election would be a good start, if only the political parties are willing to fight for the demands of the 25 January revolution; bread, freedom and justice.

Reblogged this on Ned Hamson Second Line View of the News.

LikeLike

The best and quickest way to ressucitate Egypt is to empower a strong,patriotic, wise, fervently anti-islamist and RUTHLESS leader that will force it to ressucitate. For the moment Abdel Fattah el Sissi fits best the profile above. Even if we extend this discussion space by millions light years no one will find a better alternative at the moment. May be that too is a legacy from Mubarak.

LikeLike